|

A329: The Making of Welsh History 2023

EMA

Dissertation

By Margaret Sadler

F2467874

This entire course of study

of which

this Dissertation is part

is dedicated to my daughter

Lindsey Mae Sadler

(27th August 1981 - 6th July 2021)

Posthumous MA graduate

at the

Institute of Historical Research

London University

2019-2021

CONTENTS

Chapter 1 Introduction

Chapter 2 Building the Welsh communities

Chapter 3 The Welsh Language and cultural traditions In Liverpool

Chapter 4 Conclusion

List of illustrations

Bibliography

Chapter 1 Introduction

‘For generations, people went away from home because that was the only way to

sustain the home and family. Emigration and exile, the journey to and from home,

are the very heartbeat of Welsh culture.’ (Davies, R, (2015) p.170).

While the port of Liverpool was an assembly point for those emigrating to

world-wide destinations, it was also a popular destination for many Welsh

immigrants in search of employment and a better standard of living. Lord Mostyn

in 1885, made the comment in his inaugural address to the Liverpool Welsh

Association that, ‘Year after year, Liverpool becomes more than ever the

metropolis of Wales.’ (Cooper, K J, 2011, p.155). But, before 1885 there had

been centuries of a Welsh presence in Liverpool. The research, undertaken for

this dissertation, will give an account of the pioneering spirit, which was not

just limited to the people emigrating across the world, but also accompanied

those tentative steps of Welsh migrants experiencing Liverpool as an urban

frontier town during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Rees suggests that, ‘Welsh Methodism has known well the venturesome

pioneering spirits in Liverpool…. those who came to settle on Merseyside amply

displayed the spirit of adventure and enterprise.’ (Rees, D B (2021) p.17). To

get to Liverpool wasn’t easy, but for the link by sea on the sloop named Darling

which ran from Holyhead through the Menai Straits to Liverpool, between 1781 and

1897. Alternatively, people would have to walk most of the way, taking a ferry

across the River Dee from Flint to Parkgate

then walk to Eastham to take the ferry across the river Mersey, all this

dependent on good weather. (Rees, D B (2021), pp.25-26). To have reached their

destination following such a journey, displayed the pioneering spirit and proved

the determination of the Welsh migrants to succeed. They also brought their

much-needed labour force to a growing city and thriving port.

Initial research will focus on the foundation and expansion of the Welsh

nonconformist communities, together with their language, their traditions, and

unique culture. The Welsh population had a reputation for hard work, as Picton

observed, ‘On the whole they are an industrious, steady and sober race.’ (Picton,

J A (1875) Vol.2 p.353). This solid reputation was welcomed and sought after by

the many established Welsh building firms in Liverpool. The contribution the

Welsh building firms made to the nonconformist communities in Liverpool will be

discussed further in the next chapter. The Welsh Architects and building firms

played a significant role in enabling the Welsh speaking population to meet and

worship together in their own chapels and also enabled the overall expansion of

the Welsh communities throughout the city. The initial question, therefore, to

be addressed within this dissertation is: ‘To what extent did the Welsh

nonconformist chapel communities contribute to Liverpool’s heritage?’

Based on the facts the research will disclose, the evidence will show that

not only did the Welsh migrant population bring their pioneering spirit and

enterprise to Liverpool, but also made a lasting contribution to the landscape,

and cultural heritage of this great city which, in part, is still evident in the

twenty-first century. In order to do that, it has been necessary to delve into

the archives of Liverpool’s substantial history, alongside the history of

nonconformity and uncover the pieces of relevant information where both those

lines cross.

Many historians have contributed in the past to the subject of migration, and

Welsh migration in particular, including Colin Pooley, Dr. D Ben Rees, R Merfyn

Jones, Kathryn Cooper, Gareth Carr, Pryce, Drake, Jenkins, and many more that

are not mentioned here, many of whom will be referred to through the pages of

this dissertation. But there has to be a starting point. The aim, therefore, is

to discover the various contributory factors that led to the first Welsh

Calvinistic Methodist Chapel being built and the subsequent increase in Welsh

nonconformist chapels in Liverpool and the communities that grew up around the

city.

It has been suggested that in their new cultural setting, many became more

aware of their Welshness which was not possible in their homeland. ‘To be Welsh

in Wales was unremarkable: to be Welsh in Liverpool was to be visible, and to be

conscious of that position’ (Jones and Rees, (1984) p.34). Therefore, if indeed

there was an enhanced sense of pride in their Welshness, the second question to

be addressed is: ‘in what ways did that Welshness project out of the migrant

communities to make a lasting impression on the Liverpool urban environment?’

The success of the Welsh building firms was dependent upon good quality raw

materials and the availability of skilled and unskilled labour. It was,

therefore, essential for the firms to maintain the established links with the

suppliers of raw materials back in the Principality that they could rely on and

also for the necessary labour required to undertake demanding building

schedules.

The research has revealed that the Welsh chapels were by no means the first

nonconformist churches in Liverpool. The first Methodist chapel in the city was

of the English Wesleyan denomination. It was also the first Wesleyan chapel to

open in the north-west of England; it was opened in Pitt Street in 1750, very

much a dockland area (dmbi on-line). According to Rees, John Wesley was no

stranger to Liverpool and preached at the Pitt Street chapel many times to huge

congregations, often at 6 o’clock in the morning (Rees, D B (2021) p.27). Pitt

Street chapel near the river Mersey, welcomed many Welsh newcomers before the

Welsh Chapels began their long history in the city. This aspect of the English

Wesleyan Chapel welcoming Welsh newcomers will be discussed in more detail in

the next chapter, as it leads into the process by which the first Welsh

Calvinistic Methodist Chapel was built.

Liverpool in the late eighteenth century was an overcrowded urban city with

an increasing population. Immigrants arrived not only from Wales, but many

thousands from Ireland, particularly during the 1840s because of the famine

following the failure of the potato crops in that country, (Picton, J A (1875)

Vol.1 p.499). Newcomers also came from Scotland and many other European

countries, adding to the cosmopolitan atmosphere of this urban city and thriving

port. Alongside the benefits in the urban towns through the many avenues of

available employment, there were also obvious risks as there were in other

urban/industrial towns in England and Wales. Risks were symptomatic of the

influx of migrant populations living in overcrowded, squalid accommodation.

The Welsh migration story is a fascinating one. The extensive contribution

made to Liverpool by the people of the Principality seems to have almost been

forgotten, apart from by the historians and the descendants of those pioneers

that migrated to Liverpool in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Through

hard work, traditional cultural values, and their pioneering and venturesome

spirits they gave so much to the city that has been referred to as the

‘Metropolis of Wales.’ (Cooper, K J (2011), p.155).

Chapter 2 ‘The building of the Welsh communities’

The majority of the Welsh people that migrated to Liverpool were from the

rural counties of north Wales, taking with them their traditional rural Welsh

culture, unique language and religion which, with the nonconformist chapel at

the centre, held the communities together. But it should be remembered that,

during the Georgian period, when urban town populations were growing rapidly,

the port of Liverpool became an extremely overcrowded, cosmopolitan city, at

that time, without one Welsh nonconformist chapel. The history that led to the

building of the nonconformist chapel communities in Liverpool, is discussed

below.

During the late eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century many of the

migrants arriving in Liverpool would have been accommodated in court dwellings.

Commonly called back-to-back court dwellings were three story buildings

consisting of tightly packed small rooms, approximately 10’ 6” wide and deep.

There were six or eight similar buildings surrounding a courtyard 10’ – 15’ wide

accessed by a narrow alley-way. Each court would back on to the next, densely

populated, without running water, each court housing possibly 25 or more

families, would be serviced by one shared toilet and a water standpipe in the

centre of the court. (Stewart, E J (2019) p.7). A typical room is pictured

above. The photograph taken at the Museum of Liverpool is part of the court

dwelling reconstruction.

According to Carr, the court dwellings were introduced into Liverpool through

the speculative owners of the large Georgian town-houses vacating their homes

for sub-letting and making the gardens at the rear of their properties available

for further building projects. (Carr, G (2014 p.8). This practice provided the

owners with a lucrative rental income, at the same time providing business for

the building firms, employment opportunities and in turn, much needed

accommodation for the ever-increasing migrant population.

The Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Pitt Street, referred to in the previous

chapter, was mentioned in terms of being a welcoming community for many Welsh

nonconformist migrants arriving in the city. The chapel was surrounded by court

dwellings and a number of the Welsh Methodists from the courts attended that

chapel.

According to Rees, one such member was William Llwyd from Flintshire. Llwyd,

along with some of his Welsh speaking friends, also from north Wales, were

hopeful that they would have a chapel of their own at some point in the future,

where they would be able to hold services entirely in Welsh. First, Llwyd and

his friends met in his home until there were so many people wanting to join them

that larger premises had to be found. The only large space that could be found

nearby to accommodate the meetings was in a local warehouse. The warehouse was

owned by ‘Billy the Ragman,’ the title indicating his occupation. According to

Rees, the warehouse was a very unpleasant place where people drowned in the

Mersey were laid out in their coffins, (Rees, D B, [2021] p.28).

William Llwyd was a humble early Welsh migrant, confirmed in his faith and

determined to maintain his Welsh heritage. He was instrumental in inviting

preachers from his home area in Wales to come and preach to the Welsh

nonconformist community that had grown up around the Wesleyan chapel to help

uphold the faith of all the Welsh members of the congregation of the Pitt Street

Chapel. William Llwyd had built up such a reputation that when he died in 1810,

more than one thousand people attended his funeral (Rees, D B (2162) p.28).

A Welsh visitor arrived at the Pitt Street Chapel after walking from

Anglesey. The visitor was Owen Thomas Roland, a blacksmith and lay preacher,

escaping persecution from the clergy on Anglesey. For a short while he became

another Welsh exile in Liverpool. Although Roland spoke very little English, he

was warmly welcomed by the Pitt Street congregation, and encouraged to preach to

the many Welsh monoglot members that worshipped there. He preached on the banks

of the river Mersey, and according to Rees, the beginnings of the Welsh

Calvinistic Methodist cause in Liverpool can be linked to one of the sermons he

preached at that time. (Rees, D B (2021) p.27).

Artist’s impression

of Pall Mall Chapel 1787

The Revd Thomas Charles, from Bala, was another pioneering Welshman of

eminent renown, who visited Liverpool on several occasions. According to Rees,

he made the dangerous crossing from Eastham to Liverpool on the ferry, which

almost cost him his life on one occasion, when a storm arose. (Rees, D B (2021)

pp.28-29). On a visit during 1785, Charles visited the warehouse where William

Llwyd had held his meetings with his Welsh speaking friends. Charles was

impressed by the faithfulness of the Welsh exiles, but distressed that the only

place they had to meet to worship in Welsh, was in the dreadful warehouse,

described above. When Charles returned to Merionethshire, he made it known what

terrible conditions the Welsh people in the heart of Liverpool had to endure in

order to hold a Welsh nonconformist service. Charles used his considerable

network of many contacts to begin raising funds for the Welsh community in

Liverpool to purchase a piece of land on which to build a chapel. Thanks to the

money collected throughout Wales for this cause, the first Calvinistic Methodist

Chapel was opened in Pall Mall, Liverpool on Whit Sunday in 1787. (Rees, D B

(2021) p.29). According to the Dictionary of Welsh Biographies (DWB), Thomas

Charles of Bala, began his life as an Anglican Clergyman, but favoured the

evangelistic approach of the Calvinistic Methodists denomination. In 1784

Charles was formally enrolled as a member of the Methodist Society. Charles was

instrumental in the provision of Welsh Bibles, and also initiated the

continuance of the circulating schools originally developed by Griffith Jones

and Bridget Bevan (DWB). Charles was Influential in Wales, and was primarily

responsible for establishing the Welsh Sunday schools for both adults and

children. In 1806 Charles was in Liverpool to open the second Calvinistic Chapel

in Bedford Street. According to Rees Charles preached three times on that

occasion once in Welsh and twice in English. He also emphasised the need for a

day school in Pall Mall. One of Charles’ supporters in Liverpool, Peter Jones, a

teacher, who was also known within the Welsh communities as Pedr Fardd (hymn

writer) following the opening of the school, continued to teach Welsh, English

and history there for thirty-three years (Rees D B ((2021) pp44-45). Roland,

Llwyd and particularly Charles were all contributory factors in the initial

establishment of the Welsh nonconformist communities in Liverpool, or more

precisely according to Rees, the establishment of the Welsh Calvinistic

Methodist denomination in Liverpool. There is another important contributory

factor in the development and expansion of the Welsh nonconformist chapels, that

will be touched upon in more detail presently. That is the contribution made by

those that built the chapels and subsequently the housing developments that

followed.

But, during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth-centuries, at the time

when Charles, Roland and Llwyd were promoting the Welsh nonconformist cause in

Liverpool, the court dwellings undoubtedly provided similar living conditions to

the squalid overcrowded conditions found in any urban/industrial town during

that period in England or Wales. These conditions and the constant increase in

the Liverpool population, brought great health risks. According to Picton,

during the spring and summer of 1832, Liverpool was struck, in common with many

towns in the country, with a cholera epidemic. The first recorded case was on

4th May, and the disease continued through the summer until autumn of that year.

Almost 5,000 people contracted the disease and there were 1,523 fatalities. (Picton,

J A (1878) Vol 1, pp,443-444). The port did not close during that period, and it

was recorded that the migrant ship Brutus sailed for Quebec on 18th May with 330

passengers. Following the outbreak of cholera on board on 28th May, the captain

eventually had to turn back to Liverpool following the death of some members of

the crew and passengers. A total of 97 people died on board. (Picton, J A,

(1878) p.444). After ten years conditions had not improved. Carr informs us that

in 1841 it was estimated that 56,000 people, approximately one-fifth of the

population of Liverpool, were still living in the squalor of court dwellings.

(Carr, G (2014 p.8)

In 2018 the National Museums Archaeological Department undertook an

excavation in Pembroke Place, Liverpool to uncover some of the original court

dwellings that were prolific around that area during the eighteenth and early

nineteenth centuries. Because of their findings, they were able to produce a

reconstruction of a court dwelling which is situated within the Museum of

Liverpool. (Pictured here)

The Liverpool town authorities did what they could to enforce the newly

introduced sanitary and housing bye-laws but it was a slow process. (Carr, G

(2014 p.8) In 1842 the Liverpool Building Act was introduced. The Act stipulated

that there should be a minimum width of fifteen feet between dwellings within

the new courts, with a requirement of ventilation space for any property that

was two rooms deep. The Sanitary Act followed in 1846 prohibiting more than

eight houses in any one court, (Carr G. 2014 p.9). The Act was amended in 1864

requiring that courts should open onto a public highway at each end being at

least twenty-five feet in length. These new rules meant that the design of

housing, in order to be as profitable as the court dwellings, had to change.

This endeavour resulted in the archetypical ‘terraced streets’ some of which are

still standing in Liverpool today. Their enterprise in the building trade was

also often admired: ‘while the city council has been peddling for years with the

question of artizans dwellings, this enterprising firm of Welshmen have solved

it.’ (Pooley, C G (1983) p.298)

It is not possible here, to relate a complete history of the many Welsh

building firms that were in existence in Liverpool during the late

eighteenth-century and through the nineteenth century. In touching on this

aspect of Welsh migration history, it has been necessary to be discerning. One

Welsh architect that was one of the most prolific and talented that migrated to

Liverpool was Richard Owens. Owens not only designed and built several of the

nonconformist chapels in Liverpool, he also provided more than 250 chapels in

both England and Wales. (Jones, J R (1946) p.97). Owens originated from

Caernarfonshire and moved to Liverpool in the 1840’s to pursue his trade as a

joiner. He joined the firm of Williams and Jones, surveyors and estate agents

where he acquired some understanding of land and building development. Also,

through his own initiative became a night-school student at the ‘Mechanics

Institute’, in Mount Steet, Liverpool and studied to become an architect. He

achieved this goal and opened his own office in Everton Village, Liverpool, when

he was just thirty-years-old. It was the start of a long relationship with the

city and the nonconformist chapel communities in both England and Wales. (Jones,

J R (1946) p.97).

During the second half of the nineteenth century the Liverpool township

boundaries were being pushed out from the overcrowded centre into districts such

as Kirkdale, West Derby, Everton and Toxteth Park. But the building firms may

not have prospered so well and easily, if the supply chain and business links

had not been maintained with the north Wales was a rich source of labour for the

ever-fervent employment market in Liverpool. Prior to the development of new

transport systems, better roads, and railways, the main transport and business

links between north Wales and Liverpool were via coastal navigation routes from

Beaumaris and Amlwych in Anglesey straight into the port. These Welsh raw

materials were of the best quality, Owens insisted upon, particularly for the

many nonconformist chapels he was responsible for in both Liverpool and Wales,

which numbered some 250 in all. Owens’ first chapel in Liverpool was built in

Fitzclarence Street in Everton (pictured above), but was destroyed during the

bombing of the second world war. (Jones J R (1946) p.98) Owens also designed

other buildings in Liverpool, warehouses in the dockland area, and also a most

prestigious office building, Westminster Chambers in Dale Street, not far from

the Town Hall. Originally designed for the firm of David Roberts, Son & Company

that became the established headquarters of Owens’ firm for the next eighty

years until the firm of Richard Owens and Son was taken over by H A Noel Woodall

architect in ‘January 1969. While working on the Mynydd Seion chapel, in

Abergele, north Wales (pictured above). Owens was in contact with the

Liverpool-based land surveying firm of David Roberts & Company, which became one

of the leaders in Liverpool’s house building industry. In collaboration with

David Roberts, Owens was responsible for the design of more than 10,000 terraced

houses in Liverpool, some of those houses in Toxteth are still in existence

today and commonly known as the Welsh streets. (Carr, G (2014 p.11) Each street

has a Welsh name. (pictured here) Wynnstay Street, Voelas Street, Rhiwlas

Street, Powis Street, Madryn Street, Kinmel Street and Gwydir Street. The fact

that the Beatles’ Drummer, Ringo Starr was born in No. 9 Madryn helped when the

local residents petitioned for the streets to be retained under the threat of

demolition some years ago, (Rees, D B (2021) p.162) Many of them underwent major

modifications in recent years but they remain a monument to the contribution

made to Liverpool by Welsh builders. Hugh Owen, Richard Owen’s son, born in 1862

continued to manage the family firm of Richard Owen & Son, until his death in

1942. Hugh was an Associate member of the Liverpool Architectural Society and

his firm remained associates of David Roberts, Son & Company, for which Hugh was

the surveyor. Together the firms were responsible for much of the outskirts of

the city of Liverpool and like his father, Hugh was the architect of many

nonconformist churches in north Wales and in Liverpool. (Jones J R (1946) p.98).

The physical aspect of building the Welsh communities was just one part of

the Welsh contribution to Liverpool. The Welsh language, and traditional culture

thrived within the nonconformist chapels. Some of these elements of Welshness

became part of every-day life in Liverpool, and will be discussed in the

following chapter.

Chapter 3 ‘The Welsh language, and cultural traditions in Liverpool

Within the close-nit Welsh communities in Liverpool, the Welsh language

thrived. As Picton wrote, ‘Everton is the Goshen of the Cambrian race …. A large

part of its population is from the Principality. Placards in the Welsh language

may be seen on the walls and Welsh newspapers in the shop windows.’ (Picton A J,

(1875) Vol 2 p353) Picton’s volumes were published in 1875, but at the beginning

of the nineteenth century, an eleven-year-old, John Jones, born in the Conwy

Valley moved to Liverpool and was apprenticed to the printers, Joseph Nevetts &

Co in Castle Street. Through the years he worked hard and became manager and by

1832 when Joseph Nevett died, the company was taken over by the Welsh-speaking

John Jones. According to Rees, Jones was a friend of Pedr Fardd, the hymn

writer, also known as Peter Jones, the teacher at Pall Mall school, featured in

the previous Chapter, he was a supporter of the Revd Thomas Charles. Several

Welsh periodicals and newspapers were published in Liverpool through the 1830s

that did not last, but in 1843 a talented Welshman, the Revd William Rees, known

by his bardic name, Gwilym Hiraethog moved to Liverpool. In collaboration with

John Jones produced Yr Ymserau (The Times) according to the description given in

the Welsh Libraries collection, it was the first Welsh newspaper to become

successful. It became really popular when the editor, John Jones, began

publishing a series of essays in the paper entitled 'Llythyrau 'Rhen Ffarmwr'

(Letters from the old farmer). The essays were written in a Welsh rural dialect

and concerned with current issues and troubles that appealed to ordinary Welsh

people. (Welsh Library Collections on-line).

During the period of time covered by Picton’s history, other aspects of the

Welsh language and culture continued to flourish, not only in Everton, but also

within the Welsh chapels around the city. The Welsh tradition that was a

constant within chapel life was music, as it had been throughout the history of

nonconformist chapels, and the Calvinistic Methodist revival lead by Howell

Harris (1714-73) in the Principality. (Jenkins, G H (2007) p.163).

From earliest times the music of Wales was recognised as being unique to the

Principality. Giraldus Cambrensis (c1146-1223), known as Gerald the Welshman and

archdeacon of Brecon. Gerald was a traveller and a keen observer and interested

in every aspect of Welsh life. Gerald was appointed by the Government of Henry

II in 1188 to tour Wales and write an account of their habits and cultural

activities (Pugh, N. 2007) pp.17-18). According to Gerald:

‘They do not sing in unison like other inhabitants of other countries, but in

many different parts so that in a company of singers …you will hear as many

different parts and voices as there are performers’ (Giraldus Cambrensis, (1188)

Bk1, Ch. XIII, p.145)

Giraldus describes Welsh choral singing, which has survived in many different

guises through the centuries. It was certainly part of the Welsh culture in

Liverpool, through the Welsh chapel choirs, and the talented musicians that had

been in the right place at the right time to encourage and nurture the

continuance of Welsh choral singing.

John Ambrose Lloyd

In 1830 a very talented fifteen-year-old boy from mold, north Wales, called

John Ambrose Lloyd, had come to Liverpool to join his brother Isaac. At that

time Isaac was a schoolmaster and editor of the Liverpool Standard and his

brother John, had come to join Isaac in his school to gain experience to become

a teacher. The Lloyd brothers were the sons of a Baptist local preacher from

Mold, in north Wales, who had migrated to Warrington. (Pugh, N (2007). Soon

after John arrived, Isaac was appointed editor of the Blackburn Standard and

left Liverpool to take up his new appointment, but John stayed in Liverpool and

became an assistant schoolmaster at a private school. Following that initial

teaching experience, he was appointed to the staff of the Picton school and in

1838 Lloyd was appointed one of the teachers at the Mechanic’s Institute. (The

school was later to become, the Liverpool Institute for boys, in Mount Street).

(NLW, biography). When his brother Isaac left Liverpool in 1835, John joined the

Tabernacle Congregational church, where Lloyd’s cousin, the Revd William Rees

was a member, and also a keen musician (NWL biography). Lloyd had joined the

Liverpool Philharmonic Society where he met several keen musicians with fine

voices. Lloyd and Rees, along with the friends Lloyd had made at the Liverpool

Philharmonic Society, gathered at Lloyds home every week for singing practice.

Together Lloyd and Rees were instrumental in establishing the first Welsh Music

Society. This group became known as the Liverpool/Welsh Choral Society, under

the leadership of John Ambrose Lloyd. (Pugh, N. (2007, p.24). At that time,

Lloyd would not have had any idea how valuable his short contribution was

destined to become, within the history of the union between Liverpool and Welsh

Choral singing. Employment hopes for Lloyd did not work out the way he had hoped

in Liverpool and in 1848 he accepted the post of manager of the north Wales

branch of the tea merchants, Woodall and Jones. Because of the travelling

involved it became necessary for Lloyd to leave Liverpool, first a move to

Chester followed by another to Conwy. John Ambrose Lloyd was just one of the

many talented Welsh people associated with the nonconformist chapels in

Liverpool, who had made a short, but vital contribution to upholding Welsh

culture in the Liverpool urban environment. (Rees, D B (2021) p.100).

No record can be found of what happened to Lloyd’s choir following his

departure, but according to Pugh, there were several attempts to gather choirs

together from the nonconformist chapels in Liverpool, throughout the 1860s.

(Pugh N (2007) p.27). In 1880 the Calvinistic Methodist Chapels united to form a

large choir with Mr John Parry as its conductor. The choir gave regular concerts

at various venues, including St. George’s Hall. The Douglas Road Welsh Chapel

had a talented precentor, Sam Evans. Evans formed and trained a mixed voice

choir of 150 at Russell Road chapel and some years later Evans became deputy

conductor of the Liverpool Welsh Choral Union (Pugh, N (2007) p.25).

During the same year (1880), a seven-year-old boy called Harry Evans was

appointed organist of the Dowlais Congregational church in south Wales. Dowlais,

at that time, was considered to be the music centre of the south Wales valleys,

where every aspect of musical talent was encouraged. According to Pugh, the

boy’s musical talent was such that the congregation of the chapel paid for him

to have piano lessons. Harry Evans was considered to be a prodigy, and through

the succeeding years, through study and hard work he achieved the degree of

Fellow of the Royal College of Organists (FRCO). Evans then became the

accompanist of the Dowlais Choral Society and gained experience conducting large

choral events with full orchestral accompaniment.

Harry Evans

26 Princes

Avenue

Evans went on to form a male voice choir of 100 that would compete in the

1900 Eisteddfod held in Liverpool. This preparation for the Eisteddfod took

precedence over everything in Evans’ life. The Male Voice Choir from Dowlais

took first prize out of eleven choirs that participated in the competition, and

the only choir during the whole of the Eisteddfod won by competitors from Wales.

(Pugh, N (2007), pp.49-50). In 1902 Harry Evans was appointed Chorus Master and

Principal Conductor by the founders of the Liverpool Welsh Choral Union, and as

the Liverpool choir became a more important part of Evans’ life, he moved from

Dowlais to his new home at 26 Princes Avenue, in Toxteth, Liverpool, a very

fashionable part of town in the early 20th century. The house has been well

restored and is now several apartments. Also, at that time he was appointed

organist and choirmaster of Great George Street Congregational Church. According

to the detail recorded in the Dictionary of Welsh biographies, as well as being

the conductor of the Liverpool Welsh Choral Union, in 1913, he also became the

musical director at Bangor University College and in the same year, local

conductor and registrar of the Liverpool Philharmonic Society. This appointment

recognised his great talent as a conductor, and it also meant that he was able

to share his talent, not only with the Welsh people in Liverpool, but with the

wider spectrum of English musicians in the city.

The Liverpool Welsh Choral union that had its beginnings many years before

with John Ambrose Lloyd, was destined to continue for many years with very

talented Welshmen as choral conductors and famous Principal conductors, such as

Sir Malcolm Sargent, and Maurice Handford and Patrons include William Mathias,

CBE, and Karl Jenkins OBE from 2005 until the present. (Pugh, N (2007) The

Liverpool Welsh Choral Union is still actively performing regularly at the

Philharmonic Hall in Liverpool, and at many other venues. The most recent

concert held at the Yoko Ono Lennon Centre, within Liverpool University complex

on 10th June 2023, included works by Mozart and Haydn. (https://lwcu.co.uk/).

Mixed-voice and male voice choirs were only two of the classes included

within the Eisteddfod programmes, held at various destinations in Wales and of

course, in Liverpool, in 1840, 1844, 1900 and 1929. (Pooley, C G (1983) p.299).

Brass bands, poetry, and essays, were some of the classes included from

nation-wide participants. The Transactions of the Royal National Eisteddfod of

Wales, Liverpool, 1884, edited by William R Owen, gives complete details of the

entire proceedings of that Eisteddfod. Also, the lengthy introduction by the

editor, was in praise of the Eisteddfod in Liverpool, and its value to all

Welshmen. Owen also expresses the view that it would be interesting to trace the

rise and progress of the Welsh nationality in Liverpool, and expresses hope

that, ‘some trustworthy and enlightened historian may be found to undertake the

task,’ (Owen, W R (1885) p. xvii). Every item that was adjudicated within the

1884 Eisteddfod was published within the volume.

The Welsh newspapers such as Y Cymro, produced in Liverpool printed articles

and notices in both Welsh and English. The English-language Liverpool Mercury

also provided space for Welsh news, which as Pooley suggests helped to unite

both the Welsh and English communities (Pooley, C G (1983) p.299). It provided

the reports of events held within the network of clubs and Eisteddfodau which

served the working-class Welsh communities. The North Wales Chronicle of

Saturday 20th September 1884 reported on the National Eisteddfod in Liverpool.

The lengthy report in English, paid tribute to all the choirs taking part in the

‘Great Choral Competition,’ which was won by the choir from Bethesda in north

Wales, for the third successive year and given the prize of £200.

According to Rees, by the early twentieth century most chapels held their own

Eisteddfod, along with various other organisations. The Red Dragon eisteddfodau

was set up not only to strengthen the Welsh language in the city but also to

bring poets and writers together. The resulting eisteddfodau encouraged national

competitors and renowned adjudicators. (Rees, D B (2021) p.220). Successful

businessmen in the city were invited to be presidents of the Red Dragon

eisteddfod. One such president was William Lewis, head of the Liverpool based

Pacific Steam Navigation Company. The Welsh students at Liverpool University

held their own eisteddfod, as did the Lewis’s department store. (Rees, D B

(2021) pp.215-219). Other cultural organisations grew out of the Eisteddfodau,

and the Cymric Male Voice Choir stemmed from that festival. The sixteenth Annual

Concert of the Cymric Male Voice Choir was advertised on page 4 of Y Cymro dated

1st March 1900. The concert was to take place at Hope Hall in Hope Street,

Liverpool on the evening of 3rd March. The fact that it was the choir’s

sixteenth annual concert, would suggest the choir came into being in 1884, the

year of the second National Eisteddfod in Liverpool.

The Liverpool Welsh National Society was formed to serve the increasing

number of middle and upper-class Welsh businessmen and professionals that had

made their homes in the city. The all-male list of officers of the society

included: The Rit. Hon. Lord Mostyn, as President; vice Presidents included His

Imperial Highness Prince Louis-Lucien Bonaparte; Lord Aberdare, Lord Boston, and

many other Lords, members of parliament, professional people, professors and

other people of note. (Library of Wales, Journals LWNS (1885) p.iii). The rules

of the society were designed to promote the following: The National interests of

Wales; The social intercourse between Welshmen in Liverpool and the welfare of

Welshmen in general; Literature, science and art, as it is connected with Wales;

The formation in Liverpool of a library of Celtic literature. The list

continues, basically to provide for the cultural needs of the upper- classes of

Welshmen of the city. No women were included. The annual dinner was to be held

at the Adelphi hotel for one-hundred gentlemen. (LWNS), (1885 p.iv). The tickets

for the annual dinner to be held on St. David’s Day in 1900 were priced at 5s/6d

each for both ladies and gentlemen, and advertised on 1st March 1900 in the news

paper Y Cymro. By the turn of the century all levels of the Welsh population

were catered for in terms of places of worship, suitable housing, and cultural

activities. The Welsh population had settled successfully in the English urban

environment and in doing so had contributed a unique chapter into the social and

cultural history of this great city.

Chapter 4 Conclusion

The research undertaken on the subject of Welsh migration to Liverpool has

proved to be a fascinating journey of discovery. The various avenues of research

followed, have led to revealing an almost forgotten, but substantial part of the

history of Liverpool. Several examples of the bricks and mortar of that history

still remain in Liverpool to be admired and are referred to within the text

above. The building projects undertaken in Liverpool during the nineteenth

century were the initiative of Welsh building firms that employed Welsh labour

and created Welsh communities. The new housing developments were a response to

the overcrowding and terrible living conditions created during the late

eighteenth-century when court dwellings were introduced into the city. At that

time in Liverpool, as with many other urban industrial towns in England,

overcrowding was caused by the influx of migrants from Wales, Scotland, Ireland,

and from many European countries arriving through the port.

By researching the building and expansion of the nonconformist communities in

Liverpool, many other facts were uncovered in relation to the housing shortage

at that time, the overcrowded conditions of the court dwellings providing a

breeding ground for disease, hence the cholera outbreak in 1832, and the efforts

by the city to correct some of the faults. New by-laws were brought into effect

regarding the size of the courts and ventilation to make healthier living

conditions. It was inevitable that a solution had to be reached and at the same

time as the Welsh builders were providing chapels for Welsh services, they were

also providing the housing solutions for the ever-expanding city. As Pooley

suggested in Chapter 2 above, while the city council has been peddling for years

with the question of artizans dwellings, these enterprising firms of Welshmen

have solved it.’ (Pooley, C G (1983) p.298).

But, the initial aim of this dissertation was to chart the expansion of the

Welsh nonconformist communities throughout the city. It purported to do this by

giving an insight into the people involved in the initial establishment of Welsh

nonconformist chapels in Liverpool, and how their endeavours resulted in the

first Welsh Calvinistic Methodist chapel being built in Pall Mall in 1787. Among

the people involved in the conception of the Pall Mall Chapel, were in fact the

Welsh migrants that were welcomed into the Wesleyan chapel built in Pitt Street,

in 1750 where John Wesley had preached. They included William Llwyd, who lived

behind the chapel, probably in one of the infamous court dwellings. There was

also the blacksmith, lay preacher who walked from Anglesey, Owen Thomas Roland,

who preached to the Welsh members of the chapel on the banks of the Mersey. It

was the desire and hope of those people that inspired the Revd Thomas Charles

from Bala to initiate raising the funds to build the first Welsh Calvinistic

chapel in Liverpool, in Pall Mall, then the second in Bedford Street a little

south of the city centre. From that time through the nineteenth century the

Welsh chapels and the communities became more prevalent throughout the city. The

information detailed in chapter II above provides evidence of the contribution

made by the Welsh architects and builders that provided the foundations for the

Welsh communities to exist in Liverpool and enabled the communities to thrive

using their unique Language and engage in the cultural activities that are

reflected in the details given in Chapter III above.

Research into the more aesthetic side of Welsh history in Liverpool played a

significant part in answering the initial question posed which was, ‘to what

extent did the nonconformist chapel communities contribute to Liverpool’s

heritage?’ A balanced assessment of the information gathered suggests that the

Welsh communities throughout the late-eighteenth and nineteenth century

maintained their Welshness, through the continued use of their unique language,

and their various cultural pursuits. The great Liverpool historian, James

Allanson Picton records the fact in his famous publication, Memorials of

Liverpool, as he writes, ‘Everton is the Goshen of the Cambrian race, there are

chapels where the services are conducted in the Cambrian tongue, and there are

Welsh placards on the walls and Welsh newspapers in the shops.’. (Picton J A

(1785) p.353). One of the traditional Welsh cultural activities that was a

constant within the nonconformist chapels was music. Research revealed each

chapel had its own choir, depending on the precentor, some of the choirs were

larger, or better than others, some chapels had musical organisations that grew

out of the chapel choir, as the details above will attest. Male voice choirs

were, and still are a great tradition in Wales, as well as mix-voiced choirs

that also grew out of the nonconformist chapels.

The chapels were the hub through which all the Welsh chapel communities in

Liverpool were linked, and it was through that communication system that it was

possible to unite choirs from various chapels to gather voices together to

produce a choir of a sufficient standard to participate in Eisteddfods that were

held, at local and national level, in Liverpool. There was one choral group that

appeared during early nineteenth century that proved to be a catalyst for a

combination of Liverpool/Welsh endeavour, that was the Liverpool Welsh Choral

Society, that eventually became the Liverpool Welsh Choral Union, that has

survived the test of time through the years of its metamorphosis to what the

choir is today in Liverpool.

The research undertaken in order to answer the question: to what extent the

Welsh nonconformist chapel communities contributed to Liverpool’s heritage, is

revealed through the facts stated above. There is still much of the evidence of

the nineteenth century Welsh contributions to Liverpool that are still visible

in the city today. The recently modernised Welsh housing in Toxteth is a

wonderful tribute to the Welsh people that built the original homes. Several of

the Welsh Chapels are still being used, if not for worship, or worship in the

Cambrian tongue, they have been converted into luxury apartments. In terms of

the cultural side of the contribution, the Liverpool Welsh Choral Union is still

performing in the City, their latest concert is detailed in Chapter III above.

There is no doubt that further research could record the eventual process of the

Welsh communities becoming more Anglicized as generation followed generation

within Liverpool. But the research undertaken for this dissertation demonstrated

the sentiments expressed by the Revd Dr D Ben Rees, when he wrote, ‘Welsh

Methodism has known well the venturesome pioneering spirits in Liverpool …those

who came to settle on Merseyside amply displayed the spirit of adventure and

enterprise.’ (6,901 words)

List of Illustrations

1. Photograph of a Court dwelling single room. Part of the

Court dwelling reconstruction at the Museum of Liverpool

(my own photograph)

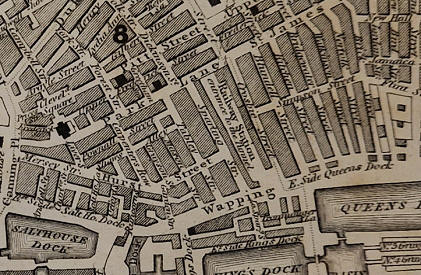

2. Pitt Street Chapel (early nineteenth century street map)

Liverpool City Archivists Department Liverpool central Library

3. Artist’s impression of Pall Mall Chapel 1787

– c/o The National Library of Wales (Public domain)

4. Court dwelling reconstruction Museum of Liverpool –

Used with permission of the Museum staff - My own photograph.

5. Fitzclarence Street Chapel, Everton

https://welshchapels.wales/welsh-chapels/richard-owens/

6. Mynydd Seion Chapel, Abergele

https://welshchapels.wales/welsh-chapels/richard-owens/

Personal licence - Coflein Digital Asset Management (ibase.media)

7. The Welsh Streets, photographed following the redevelopment of

the area of the original streets as listed in the text. (My own photograph)

8. Portrait of John Ambrose Lloyd,

https://biography.wales/article/s-LLOY-AMB-1815#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&manifest=

https%3A%2F% 2Fdamsssl.llgc.org.uk%2Fiiif%2F2.0%2F4702553%2Fma (Public domain)

9. Photograph of Harry Evans, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/31/Harry_

Evans%2C_Dowlais.jpg (public domain)

10. Photograph of 26 Princes Avenue, taken 15th May 2023 - my own photograph.

Bibliography

Primary sources

www.liverpool.gov.uk/archives Liverpool Street maps and Ordnance Survey maps,

Trade and local street directories for England and Wales from the 1760s to the

1910s.

Advertising|1900-03-01|Y Cymro - Welsh Newspapers (library.wales)Y Cymro

March 1st 1900. Advertisements The Cymric Vocal Union (Male Voice Choir) on p.4

and for the Liverpool Welsh National Society, Annual Dinner on p.8.

https://newspapers.library.wales/view/4451974/4451977/10/LIVERPOOL North

Wales Chronicle, The National Eisteddfod at Liverpool. (20th September 1884)

Roberts, J., (1959). CHARLES, THOMAS (1755 - 1814), Methodist cleric.

Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 14 May 2023, from https://biography.wales/article/s-CHAR-THO-1755

https://manchestervictorianarchitects.org.uk/index.php/architects/richard-owens

Re: Richard Owens, Architect, Liverpool.

Directory of Methodism of Britain and Ireland

http://dmbi.online/index.php?do=app.entry&id=1718

https://journals.library.wales/view/2043441/2043442/#?m=&xywh=521%2C306%2C1580%2C1497&cv=3

Transactions of the Liverpool Welsh National Society 1885.

Secondary Sources

Carr, G, (2014), Lecture delivered at the Festival of Welsh Builders,

https://www.liverpool-welsh.co.uk/archive/The%20Welsh%20Builders.pdf

Cooper, K J, (2011) Exodus from Cardiganshire – Rural-Urban Migration in

Victorian Britain, Cardiff University of Wales Press.

Giraldus Cambrensis, “Of their Symphonies and Songs”, Bk.1, Ch. XIII, A

Vision of Britain Through Time (Oxford, 1997), The Description of Wales by

Gerald of Wales, First Preface, To Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury.

P.145.

Jones, J R (1946), The Welsh Builder on Merseyside: Annals and Lives.

Published by J R Jones, Menlove Avenue, Liverpool. (Liverpool City Archivists

Department)

Jones, R M and Rees D B (1984) Liverpool Welsh & Their Religion, Modern Welsh

Publications Ltd, Allerton, Liverpool and Llanddewi Brefi, Dyfed.

Picton, J A, (1875), Memorials of Liverpool, Historical and Topographical

Including history of the Dock estate; Topographical Vols 1 and 2. Reproduced by

‘Forgotten Books’ (2018).

Pooley, C G, (1983), Welsh migration to England in he mid-nineteenth century,

Journal of Historical Geography, Volume 9, Issue 3, pp.287-305.

Pryce, W T R, (1994) From Family History to Community History, p.49,

Cambridge University Press, The Open University.

Rees, D B (2021), The Welsh in Liverpool: A Remarkable History, published by

Y Lolfa Cyf, Talybont, Ceredigion SY24 5HE.

Stewart, E J, (2019) p.7 Courts and Alleys A history of Liverpool courtyard

housing, Liverpool University Press, 4 Cambridge Street, Liverpool L69 7ZU.

Liverpool/Welsh Choral Union, concert information 2023.

https://lwcu.co.uk/mozart-requiem-hadyn-theresienmesse/

|